In my Introduction to Sociology course at Kent State University at Ashtabula, students are regularly encouraged to become more engaged citizens and to embrace the diversity of their economic, political, cultural, and community-based backgrounds to make the world they live in a better place, working together in the true spirit of democracy. A group of students decided to support the hard work of local merchants in Ashtabula Ohio to keep the community alive with great food, drink, local spirit and material goods. So, they held a cash mob on the Harbor Area down on Bridge Street.

Here is a fun video of the event put together by Tina Bihlajama and Frank Vaccariello--CLICK HERE

Translate

06/05/2012

27/04/2012

Pedaling Art 2012 Ohio City Bike CO-OP Art Show

Hello everyone! It is time for the annual Pedaling Art Show to benefit the awesome Ohio City Bicycle CO-OP. As the poster below explains, any art dealing with or using bicycles is welcome to be submitted for possible showing!

This year, as shown below, my daughter and I went down to the CO-OP to search through all the wonderful recycled parts and decided to make bicycle jewelry.

We call our works Wheels & Gears Jewelry. We made over 20 pieces of bicycle jewelry--rings, bracelets and necklaces--all made from recycled bicycle parts. They will all sell for $15 to $20 dollars. What makes the pieces super cool is that they were all assembled entirely of bicycle parts. No welding or soldering involved.

This year, as shown below, my daughter and I went down to the CO-OP to search through all the wonderful recycled parts and decided to make bicycle jewelry.

We call our works Wheels & Gears Jewelry. We made over 20 pieces of bicycle jewelry--rings, bracelets and necklaces--all made from recycled bicycle parts. They will all sell for $15 to $20 dollars. What makes the pieces super cool is that they were all assembled entirely of bicycle parts. No welding or soldering involved.

24/04/2012

ArtCares 2012 Benefit and Art Auction for the AIDS Taskforce of Greater Cleveland

This Friday is ArtCares 2012, the annual art auction and party to benefit the AIDS Taskforce of Greater Cleveland. I have submitted my photo-assemblage of the West Side Market (as recently part of the Cleveland Hopkins Airport Art Show) to be auctioned--CLICK HERE TO SEE PHOTO. Come along and join the event!

23/03/2012

Case-Based Modeling and the SACS Toolkit: A Mathematical Outline

Over the last year Rajeev Rajaram and I finished our article mathematically outlining the SACS Toolkit, our new case-based method for modeling complex systems, particularly complex social systems.

It was published with the Springer journal, Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory, an excellent journal run/edited by Kathleen M. Carley Carnegie Mellon University, with a great editorial board.

CLICK HERE TO SEE THE ARTICLE

Much thanks to Jürgen Klüver and Christina Klüver for allowing us to present an earlier version of this paper during their session at the 8th International Conference on Complex Systems, hosted by the New England Complex Systems Institute.

It was published with the Springer journal, Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory, an excellent journal run/edited by Kathleen M. Carley Carnegie Mellon University, with a great editorial board.

CLICK HERE TO SEE THE ARTICLE

Much thanks to Jürgen Klüver and Christina Klüver for allowing us to present an earlier version of this paper during their session at the 8th International Conference on Complex Systems, hosted by the New England Complex Systems Institute.

14/02/2012

Case Based Method and Complexity Science, Part II (The SACS Toolkit)

In my previous post for February 2012--CLICK HERE TO SEE--I introduced the concepts of case-based complexity science and its methodological extension, case-based modeling--the twin concepts I use to describe the approach being developed by David Byrne, Charles Ragin and others for modeling and studying complex systems.

My goal here is to introduce the case-based complexity science method my colleagues and I have developed for modeling complex systems. Our case-based modeling technique is called the SACS Toolkit--which stands for the Sociology and Complexity Science Toolkit.

For a more thorough overview of the SACS Toolkit, including the papers and book chapters we have written on it, CLICK HERE

THE SACS TOOLKIT

The SACS Toolkit is a case-based, mixed-method, system-clustering, data-compressing, theoretically-driven toolkit for modeling complex social systems.

It is comprised of three main components: a theoretical blueprint for studying complex systems (social complexity theory); a set of case-based instructions for modeling complex systems from the ground up (assemblage); and a recommend list of case-friendly modeling techniques (case-based toolset).

The SACS Toolkit is a variation on David Byrne's general premise regarding the link between cases and complex systems. Byrne's view is as such:

Cases are the methodological equivalent of complex systems; or, alternatively, complex systems are cases and therefore should be studied as such.

The SACS Toolkit widens Byrne's view slightly. For the SACS Toolkit:

Complex systems are best thought of as a set of cases--with the smallest set being one case (as in Byrne's definition) and the largest set being, theoretically, speaking, any number of cases.

More specifically, for the SACS Toolkit, case-based modeling is the study of a complex system as a set of n-dimensional vectors (cases), which researchers compare and contrast, and then condense and cluster to create a low-dimensional model (map) of a complex system's structure and dynamics over time/space.

Because the SACS Toolkit is, in part, a data-compression technique that preserves the most important aspects of a complex system's structure and dynamics over time, it works very well with databases comprised of a large number of complex, multi-dimensional, multi-level (and ultimately, longitudinal) factors.

It is important to note, however, before proceeding, that the act of compression is different from reduction or simpli fication. Compression maintains complexity, creating low-dimensional maps that can be "dimensionally inflated" as needed; reduction or simplifi cation, in contrast, is a nomothetic technique, seeking the simplest explanation possible.

The SACS Toolkit is also versatile and consolidating. The strength, utility, and flexibility of the SACS Toolkit comes from the manner in which it is, mathematically speaking, put together. The SACS Toolkit emerges out of the assemblage of a set of existing theoretical, mathematical and methodological techniques and fi elds of inquiry--from qualitative to quantitative to computational methods.

The "assembled" quality of the SACS Toolkit, however, is its strength. While it is grounded in a highly organized and well defi ned mathematical framework, with key theoretical concepts and their relations, it is simultaneously open-ended and therefore adaptable and amenable, allowing researchers to integrate into it many of their own computational, mathematical and statistical methods. Researchers can even develop and modify the SACS Toolkit for their own purposes.

For a more thorough overview of the SACS Toolkit, including the papers and book chapters we have written on it, CLICK HERE

02/02/2012

Case Based Method and Complexity Science, Part I (Byrne, Ragin, Complexity and Case-Based Method)

Back in May of 2009 I interviewed David Byrne, who, along with Charles Ragin, has championed the usage of case-based method for modeling complex

systems. (CLICK HERE TO SEE INTERVIEW).

Ragin's work is generally referred to as case-comparative method, or, more specifically qualitative comparative analysis. It comes in two general forms, a crisp set and fuzzy set form. Byrne's work builds on Ragin. Over the last several years, Professor Byrne has emerged as a leading international figure in what most scholars see as two highly promising but distinct fields of study: (1) case-based method and (2) the sociological study of complex systems. An example of the former is Byrne’s Sage Handbook of Case-Based Methods (1)—which he co-edited with Charles Ragin, the most prominent figure in case-based method. An example of the latter is his widely read Complexity Theory and the Social Sciences (8).

Ragin's work is generally referred to as case-comparative method, or, more specifically qualitative comparative analysis. It comes in two general forms, a crisp set and fuzzy set form. Byrne's work builds on Ragin. Over the last several years, Professor Byrne has emerged as a leading international figure in what most scholars see as two highly promising but distinct fields of study: (1) case-based method and (2) the sociological study of complex systems. An example of the former is Byrne’s Sage Handbook of Case-Based Methods (1)—which he co-edited with Charles Ragin, the most prominent figure in case-based method. An example of the latter is his widely read Complexity Theory and the Social Sciences (8).

What scholars

(including myself and several of my colleagues) are only beginning to grasp, however, is the

provocative premise upon which Byrne’s work in these two fields (including his development of Ragin's ideas) is based. His premise, while simple enough, is

ground-breaking:

Cases are the methodological

equivalent of complex systems; or, alternatively, complex systems are cases and

therefore should be studied as such.

With

this premise, Byrne adds to the complexity science literature an entirely new

approach to modeling complex systems, alongside the current repertoire of

agent (rule-based) modeling, dynamical (equation-based) modeling, statistical

(variable-based) modeling, network (relational) modeling, and qualitative

(meaning-based) method.

The name of this new approach, I think, is best called case-based complexity science. My goal here, and in the next few posts for February 2012, is to discuss this new approach. I begin with a few definitions:

My colleagues, Frederic Hafferty and Corey Schimpf and I just finished a chapter that outlines the field of case-based complexity science for Martin and Sturmburg's forthcoming book, Handbook of Systems and Complexity in Health, Springer. CLICK HERE to read a section of a rough draft of the paper.

22/01/2012

I am truly an embodied mind, a socio-biological concert of self

In my Individual and Society course I typically spend the first couple weeks (amongst other things) grounding our understanding of human symbolic interaction in a wider scientific frame, by examining the scientific 'wonder' of how life emerged and how human beings came into existence--or, at least, our best current ideas on how things happened. From my perspective, it is hard to understand social interaction without an appreciation of its connection to our biological and environmental existence and the larger and smaller eco-complex systems in which we operate.

Anyway, to prepare for these lectures I often read general summaries of the latest developments in science, which give me useful ways to frame a lot of material in a quick way that focuses on the bigger picture. In preparation, one of my favorite books is Bill Bryson's A Short History of Nearly Everything.

One of the chapters that always gets me is on the emergence of life (Ch19) and its discussion of the incredible complex and self-organizing dance done by the mind-numbingly wide number and variety of living organisms that come together to make up the human body. I so easily forget that, as human beings, we are actually a collection of millions of smaller living and nonliving forms, from amino acids and proteins to mitochondria and bacteria and so forth.

Reading this material also reminds me that our conscious, brain-based cognition--that thing that calls itself I--has a certain astigmatism. Living daily life engaged in symbolic interaction, we forget that this thing we call our self (this self-reflexive, conscious I) is actually a small part of a very complex system that is comprised of millions of living organisms which, when combined in the right way, allow us to exist as a symbol making complex living system. In other words, i forget that a person, as a distinct form of structural organization, as a distinct type of living being, emerges out of, in part, a collection of smaller living beings.

I am truly an embodied mind, a socio-biological concert of self.

05/01/2012

50 Years of Information Technology

I recently ran across an excellent online historical overview of the last 50 years of information technology that I think is very well done. It was put together by Jacinda Frost. Check it out!

OnlineITDegree: 50 Years of Information Technology.

OnlineITDegree: 50 Years of Information Technology.

Proceedings of the Complexity in Health Group

The Center for Complexity in Health announces today the launching of their new white-paper outlet, the Proceedings of the Complexity in

Health Group.

The

PCCH is an annual publication designed both to showcase and provide a

publication outlet for some of the main avenues of research being conducted in

the Complexity in Health Group, Robert S. Morrison Health and Science

Building, Kent State University at Ashtabula. These areas include

medical professionalism, community health, allostatic load, school systems,

medical learning environments and case-based modeling—all explored from a

complexity science perspective.

The

studies published in the PCHG are generally comprehensive, in-depth

explorations of a topic, meant to provide a wider and more complete empirical

and theoretical backdrop for the specific studies that scholars involved in the

Complexity in Health Group (CHG) regularly publish in various disciplinary

journals. Such an outlet as the PCHG is useful given the conventions

(e.g., page constraints and narrowness of focus) typical of most research

periodicals, which make it very difficult to publish relatively complete

statements on a topic in complex systems terms. While PCHG studies

augment, acknowledge and cite CHG work published in other venues, each PCHG

study is an original, distinct manuscript. Finally, PCHG studies are

peer-reviewed. Prior to publication each study is sent to colleagues for

review and criticism to ensure the highest quality of published proceedings

possible.

PCCH

and all of its studies are the copyright © property of the Complexity in Health Group, Kent State University at Ashtabula.

Manuscripts published in the PCHG should be cited appropriately, as in the

following example:

Castellani, B., Rajaram, R., Buckwalter,

JG., Ball, M., and Hafferty, F. 2012. “Place and Health as Complex Systems: A Case Study

and Empirical Test.” Proceedings of the Complexity in Health Group,

Kent State University at Ashtabula, 1(1):1-35.

Our

first publication is an in-depth exploration of several key issues in

complexity science and its intersection with the study of community health--CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD.

First, how does one determine the empirical utility of defining a community as

a complex system? What unique insights emerge that could not otherwise be

obtained? Second, how does one conduct a litmus test of one’s definition

of a community as a complex system in a systematic manner—something currently

not done in the complexity science literature? Third, how does one use

the methods and techniques of complexity science to conduct such a litmus test,

in combination with conventional methods such as statistics, qualitative method

and historical analysis? In our study we address all three questions, as

pertains to a case study on the link between sprawl and community-level health

in a Midwestern county (Summit County, Ohio) in the United States and the 20

communities of which it comprised.

Definitional Test of Complex Systems

Back in the spring and summer of 2010 I posted a series of

discussions about the need for complexity scientists to do a better job

of comprehensively testing the empirical utility of their

definitions--see, for example, one of the posting by clicking here. My main argument was that:

1. Most complexity science today explores only specific aspects of complex systems, such as emergence or network properties.

2. While only specific aspects are explored, these same scientists assume the full definition upon which they rely to be true in terms of their topic of study, but without empirical test.

3. The testing I recommend is not about determining if a topic is a complex system, which is useless as most things are complex systems. Instead, testing should focus on the empirical and theoretical utility of the definition used. In other words, does the definition yield new insights that could not otherwise have been obtained?

4. The testing I recommend should also link complexity method with definition. In other words, scientists need to explore how complexity methods (in particular, computational modeling, case-based modeling, qualitative method, etc) help to determine/demonstrate the empirical utility of defining a topic as a complex system.

At the end of my series of posts I argued that some sort of formal test was necessary that scholars could use to conduct such as test. Well, a year and a half later, here is our Definitional Test of Complex Systems.

The Definitional Test of Complex Systems:

The DTCS is our attempt at an exhaustive tool for determining the extent to which a complex system's definition fits a topic. The DTCS is not, however, a standardized instrument. As such, we have not normed or validated it. Instead, it is a conceptual tool meant to move scholars toward empirically-driven, synthetic definitions of complex systems. To do so, the DTCS walks scholars through a nine-question, four-step process of review, method, analysis, and results---see Table 2 above.

The DTCS does not seek to determine if a particular case fits a definition; instead, it seeks to determine if a definition fits a particular case. The challenge in the current literature is not whether places are complex systems; as it would be hard to prove them otherwise. Instead, the question is: how do we define the complexity of a topic? And, does such a definition yield new insights? Given this focus, Question 9 of the DTCS functions as its negative test, focusing on three related issues: the degree to which a definition (a) is being forced or incorrectly used; (b) is not a real empirical improvement over conventional theory or method; or (c) leads to incorrect results or to ideas already known by another name. Scholars can modify or further validate the DTCS to examine its further utility. Let us briefly review the steps of the DTCS:

STEP 1: To answer the DTCS's initial five questions, researchers must comb through their topic's literature to determine if and how it has been theorized as a complex system. If such a literature does exist, the goal is to organize the chosen definition of a complex system into its set of key characteristics: self-organizing, path dependent, nonlinear, agent-based, etc. For example, if our review of the community health science literature, we identified nine characteristics. If no such literature exists, or if the researchers choose to examine a different definition, they must explain how and why they chose their particular definition and its set of characteristics, including addressing epistemological issues related to translating or transporting the definition from one field to another.

STEP 2: Next, to answer the DTCS's sixth question, researchers must decide how they will define and measure a definition and its key characteristics. For example, does the literature conceptualize nonlinearity in metaphorical or literal terms? And, if measured literally, how will nonlinearity be operationalized? Once these decisions are made, researchers must decide which methods to use. As we have already highlighted, choosing a method is no easy task. So, scientists (particularly those in the social sciences) are faced with a major challenge: the DTCS requires them to test the validity of their definitions of a complex system, but such testing necessitate them to use new methods, which many are not equipped to use. It is because of this challenge that, for the current project, we employed the SACS Toolkit, which we discuss next. First, however, we need to address the final two steps of the DTCS.

STEP 3: Once questions 1 through 6 have been answered, the next step is to actually conduct the test. The goal here is to evaluate the empirical validity of each of a definition's characteristics, along with the definition as a whole. In other words, along with determining the validity of each characteristic, it must be determined if the characteristics fit together. Having made that point, we recognize that not all complexity theories (particularly metaphorical ones) seek to provide comprehensive definitions; opting instead to outline the conditions and challenges. Nonetheless, regardless of the definition used, its criteria need to be met.

STEP 4: Finally, with the analysis complete, researchers need to make their final assessment: in terms of the negative test found in question 9 and the null hypothesis of the DTCS, to what extent, and in what ways is (or is not) the chosen definition, along with its list of characteristics, empirically valid and theoretically valuable?

1. Most complexity science today explores only specific aspects of complex systems, such as emergence or network properties.

2. While only specific aspects are explored, these same scientists assume the full definition upon which they rely to be true in terms of their topic of study, but without empirical test.

3. The testing I recommend is not about determining if a topic is a complex system, which is useless as most things are complex systems. Instead, testing should focus on the empirical and theoretical utility of the definition used. In other words, does the definition yield new insights that could not otherwise have been obtained?

4. The testing I recommend should also link complexity method with definition. In other words, scientists need to explore how complexity methods (in particular, computational modeling, case-based modeling, qualitative method, etc) help to determine/demonstrate the empirical utility of defining a topic as a complex system.

At the end of my series of posts I argued that some sort of formal test was necessary that scholars could use to conduct such as test. Well, a year and a half later, here is our Definitional Test of Complex Systems.

The Definitional Test of Complex Systems:

The DTCS is our attempt at an exhaustive tool for determining the extent to which a complex system's definition fits a topic. The DTCS is not, however, a standardized instrument. As such, we have not normed or validated it. Instead, it is a conceptual tool meant to move scholars toward empirically-driven, synthetic definitions of complex systems. To do so, the DTCS walks scholars through a nine-question, four-step process of review, method, analysis, and results---see Table 2 above.

The DTCS does not seek to determine if a particular case fits a definition; instead, it seeks to determine if a definition fits a particular case. The challenge in the current literature is not whether places are complex systems; as it would be hard to prove them otherwise. Instead, the question is: how do we define the complexity of a topic? And, does such a definition yield new insights? Given this focus, Question 9 of the DTCS functions as its negative test, focusing on three related issues: the degree to which a definition (a) is being forced or incorrectly used; (b) is not a real empirical improvement over conventional theory or method; or (c) leads to incorrect results or to ideas already known by another name. Scholars can modify or further validate the DTCS to examine its further utility. Let us briefly review the steps of the DTCS:

STEP 1: To answer the DTCS's initial five questions, researchers must comb through their topic's literature to determine if and how it has been theorized as a complex system. If such a literature does exist, the goal is to organize the chosen definition of a complex system into its set of key characteristics: self-organizing, path dependent, nonlinear, agent-based, etc. For example, if our review of the community health science literature, we identified nine characteristics. If no such literature exists, or if the researchers choose to examine a different definition, they must explain how and why they chose their particular definition and its set of characteristics, including addressing epistemological issues related to translating or transporting the definition from one field to another.

STEP 2: Next, to answer the DTCS's sixth question, researchers must decide how they will define and measure a definition and its key characteristics. For example, does the literature conceptualize nonlinearity in metaphorical or literal terms? And, if measured literally, how will nonlinearity be operationalized? Once these decisions are made, researchers must decide which methods to use. As we have already highlighted, choosing a method is no easy task. So, scientists (particularly those in the social sciences) are faced with a major challenge: the DTCS requires them to test the validity of their definitions of a complex system, but such testing necessitate them to use new methods, which many are not equipped to use. It is because of this challenge that, for the current project, we employed the SACS Toolkit, which we discuss next. First, however, we need to address the final two steps of the DTCS.

STEP 3: Once questions 1 through 6 have been answered, the next step is to actually conduct the test. The goal here is to evaluate the empirical validity of each of a definition's characteristics, along with the definition as a whole. In other words, along with determining the validity of each characteristic, it must be determined if the characteristics fit together. Having made that point, we recognize that not all complexity theories (particularly metaphorical ones) seek to provide comprehensive definitions; opting instead to outline the conditions and challenges. Nonetheless, regardless of the definition used, its criteria need to be met.

STEP 4: Finally, with the analysis complete, researchers need to make their final assessment: in terms of the negative test found in question 9 and the null hypothesis of the DTCS, to what extent, and in what ways is (or is not) the chosen definition, along with its list of characteristics, empirically valid and theoretically valuable?

Place and Health as Complex Systems: A Case Study and Empirical Test

Back in the spring and summer of 2010 I posted a series of discussions about the need for complexity scientists to do a better job of comprehensively testing the empirical utility of their definitions--see, for example, one of the posting by clicking here. My main argument was that:

1. Most complexity science today explores only specific aspects of complex systems, such as emergence or network properties.

2. While only specific aspects are explored, these same scientists assume the full definition upon which they rely to be true in terms of their topic of study, but without empirical test.

3. The testing I recommend is not about determining if a topic is a complex system, which is useless as most things are complex systems. Instead, testing should focus on the empirical and theoretical utility of the definition used. In other words, does the definition yield new insights that could not otherwise have been obtained?

4. The testing I recommend should also link complexity method with definition. In other words, scientists need to explore how complexity methods (in particular, computational modeling, case-based modeling, qualitative method, etc) help to determine/demonstrate the empirical utility of defining a topic as a complex system.

At the end of my series of posts I noted that my colleagues and I were working on an article to address this issue, as pertains to the study of community health and school systems.

Well, a year and a half later, our study on community health is done--CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD IT. Here is the abstract:

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Abstract: Over the last decade, scholars have developed a complexities of place (COP) approach to the study of place and health. According to COP, the problem with conventional research is that it lacks effective theories and methods to model the complexities of communities and so forth, given that places exhibit nine essential "complex system" characteristics: they are (1) causally complex, (2) self-organizing and emergent, (3) nodes within a larger network, (4) dynamic and evolving, (5) nonlinear, (6) historical, (7) open-ended with fuzzy boundaries, (8) critically conflicted and negotiated, and (9) agent-based.While promising, the problem with the COP approach, however, is that its definition remains systematically untested and its recommended complexity methods (e.g., network analysis, agent-based modeling) remain underused. The current article, which is based on a previous abbreviated study and its ”sprawl and community-level health” database, tests the empirical utility of the COP approach. In our abbreviated study, we only tested characteristics 4 and 9. The current article conducts an exhaustive test of all nine characteristics and suggested complexity methods.

Method: To conduct our test we made two important advances: First, we developed and applied the Definitional Test of Complex Systems (DTCS) to a case study on sprawl—a ”complex systems” problem—to examine, in litmus test fashion, the empirical validity of the COP’s 9-characteristic definition. Second, we used the SACS Toolkit, a case-based modeling technique for studying complex system that employs a variety of complexity methods. For our case study we examined a network of 20 communities (located in Summit County, Ohio USA) negatively impacted by sprawl. Our database was partitioned from the Summit 2010: Quality of Life Project.

Results: Overall, the DTCS found the COP’s 9-characteristic definition to be empirically valid. The employment of the SACS Toolkit supports also the empirical novelty and utility of complexity methods. Nonetheless, minor issues remain, such as a need to define health and health care in complex systems terms.

Conclusions: The COP approach seems to hold real empirical promise as a useful way to address many of the challenges that conventional public health research seems unable to solve; in particular, modeling the complex evolution and dynamics of places and addressing the causal interplay between compositional and contextual factors and their impact on community-level health outcomes.

1. Most complexity science today explores only specific aspects of complex systems, such as emergence or network properties.

2. While only specific aspects are explored, these same scientists assume the full definition upon which they rely to be true in terms of their topic of study, but without empirical test.

3. The testing I recommend is not about determining if a topic is a complex system, which is useless as most things are complex systems. Instead, testing should focus on the empirical and theoretical utility of the definition used. In other words, does the definition yield new insights that could not otherwise have been obtained?

4. The testing I recommend should also link complexity method with definition. In other words, scientists need to explore how complexity methods (in particular, computational modeling, case-based modeling, qualitative method, etc) help to determine/demonstrate the empirical utility of defining a topic as a complex system.

At the end of my series of posts I noted that my colleagues and I were working on an article to address this issue, as pertains to the study of community health and school systems.

Well, a year and a half later, our study on community health is done--CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD IT. Here is the abstract:

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Abstract: Over the last decade, scholars have developed a complexities of place (COP) approach to the study of place and health. According to COP, the problem with conventional research is that it lacks effective theories and methods to model the complexities of communities and so forth, given that places exhibit nine essential "complex system" characteristics: they are (1) causally complex, (2) self-organizing and emergent, (3) nodes within a larger network, (4) dynamic and evolving, (5) nonlinear, (6) historical, (7) open-ended with fuzzy boundaries, (8) critically conflicted and negotiated, and (9) agent-based.While promising, the problem with the COP approach, however, is that its definition remains systematically untested and its recommended complexity methods (e.g., network analysis, agent-based modeling) remain underused. The current article, which is based on a previous abbreviated study and its ”sprawl and community-level health” database, tests the empirical utility of the COP approach. In our abbreviated study, we only tested characteristics 4 and 9. The current article conducts an exhaustive test of all nine characteristics and suggested complexity methods.

Method: To conduct our test we made two important advances: First, we developed and applied the Definitional Test of Complex Systems (DTCS) to a case study on sprawl—a ”complex systems” problem—to examine, in litmus test fashion, the empirical validity of the COP’s 9-characteristic definition. Second, we used the SACS Toolkit, a case-based modeling technique for studying complex system that employs a variety of complexity methods. For our case study we examined a network of 20 communities (located in Summit County, Ohio USA) negatively impacted by sprawl. Our database was partitioned from the Summit 2010: Quality of Life Project.

Results: Overall, the DTCS found the COP’s 9-characteristic definition to be empirically valid. The employment of the SACS Toolkit supports also the empirical novelty and utility of complexity methods. Nonetheless, minor issues remain, such as a need to define health and health care in complex systems terms.

Conclusions: The COP approach seems to hold real empirical promise as a useful way to address many of the challenges that conventional public health research seems unable to solve; in particular, modeling the complex evolution and dynamics of places and addressing the causal interplay between compositional and contextual factors and their impact on community-level health outcomes.

09/12/2011

Steven Pinker versus Complexity Part II

In a previous post--click here to see--I discussed Pinker's new book The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence has Declined in terms of the interest it holds for a complexity scientists working in the social sciences.

The main issue I concentrated on was his argument that, not only has violence decreased over the longue durée of human history and, more specifically, the last 20 years of globalization-induced history, but that this decrease is scale-free, from attitudes on spanking children to wars. I took issue with this argument, pointing out that it is probably much more scale-dependent and context-sensitive than he makes the argument to be. (Again, remember, in the spirit of Foucault's approach to polemics, the point of my posting on Pinker's book is to think from a complexity perspective to see if it fosters new ideas, not to tear down the work of someone else.)

I spent the next few days thinking, and I have another issue regarding this notion of violence being relatively scale-free that I wanted to address: the fact that Pinker's argument is variable-based--a perspective that case-based complexity scientists such as Charles Ragin and David Byrne, amongst others, seek to avoid. (To read more about their views, see their latest edited book, The Sage Handbook of Case-Based Methods.)

If you think about it, complex systems cannot be studied as a collection of variables. How, for example, do you study the adjacency or proximity (dissimilarity) matrix of a set of variables? Systems are made up of agents and structures and environmental forces (top-down, bottom-up, and any other direction you want to consider) which, together, are best conceptualized as cases: configurations of variables that, together, form a self-organizing emergent whole that is more than the sum of its parts, and is nonlinear, dynamic, path (context) dependent and evolving across time/space. Ragin goes even further: stop thinking of variables as variables; they are sets. Violence, for example, is not a variable. Violence is a set--fuzzy or crisp--into which cases represent degrees of membership. For example, thinking of Pinker's study, "war in the 1800s in Europe" is a case, along with another case such as "war in China in the 1800s." Both cases could be placed in the set "macro-level violence through war." Membership in the case could, at least initially, be defined in terms of basic rates, as Pinker uses, or converted into boolean or fuzzy set membership.

But the key point here is that they are different: they are each a case, a different, context-dependent case, which one will explore, in terms of their respective configurations, to find similarities and differences; and it is this comparative approach that will draw out the context-dependent causal similarities and differences amongst these cases. For example, in relation to Pinker's work, one may find that violence has gone down in both cases, but the reasons for the decrease in violence is different, based on differences in configuration.

Why is something like this important? Consider policy recommendations. Insensitivity to configurational differences, context and, ultimately complexity is the failure of much policy--see, for example, Applying Social Science by Byrne.

Following this argument, violence, as a complex system, reconfigured at multiple levels of scale, can be defined as a set, comprised of multiple sub-sets, each representing a type and scale of violence, from the macro to the micro. Each set is comprised of cases, which are configurations, which take into consideration context and difference. Such an approach allows one to talk about violence in a much more sophisticated way. For example, one could show how violence is increasing and decreasing, for example over time; contradictory trends. The macro-level violence of war in Europe during the 20th century is not the same thing as the macro-level violence of war in China or Africa or South America or between hunter and gathering tribes or war amongst smaller empires. They constitute different cases, different forms of macro-level violence. Studying violence this way allows us to ask much more specific questions: which forms of government or social organization in which particular contexts, for example, lead to less war? Which forms of government or social organization in which particular contexts lead to less micro-level, face-to-face violence? And, so forth.

The main issue I concentrated on was his argument that, not only has violence decreased over the longue durée of human history and, more specifically, the last 20 years of globalization-induced history, but that this decrease is scale-free, from attitudes on spanking children to wars. I took issue with this argument, pointing out that it is probably much more scale-dependent and context-sensitive than he makes the argument to be. (Again, remember, in the spirit of Foucault's approach to polemics, the point of my posting on Pinker's book is to think from a complexity perspective to see if it fosters new ideas, not to tear down the work of someone else.)

I spent the next few days thinking, and I have another issue regarding this notion of violence being relatively scale-free that I wanted to address: the fact that Pinker's argument is variable-based--a perspective that case-based complexity scientists such as Charles Ragin and David Byrne, amongst others, seek to avoid. (To read more about their views, see their latest edited book, The Sage Handbook of Case-Based Methods.)

Byrne's

work, for example, specifically focuses on the intersection of

complexity science and case-based method. The premise upon which his

work is based, while

simple enough, is ground-breaking: in the social sciences, cases are the

methodological equivalent of

complex systems; or, alternatively, complex systems are cases and

therefore

should be studied as such. With this

premise, Byrne adds to the complexity science literature an entirely new

approach to modeling complex systems, alongside the current repertoire

of agent

(rule-based) modeling, dynamical (equation-based) modeling, statistical

(variable-based) modeling, network (relational) modeling, and

qualitative

(meaning-based) method.

If you think about it, complex systems cannot be studied as a collection of variables. How, for example, do you study the adjacency or proximity (dissimilarity) matrix of a set of variables? Systems are made up of agents and structures and environmental forces (top-down, bottom-up, and any other direction you want to consider) which, together, are best conceptualized as cases: configurations of variables that, together, form a self-organizing emergent whole that is more than the sum of its parts, and is nonlinear, dynamic, path (context) dependent and evolving across time/space. Ragin goes even further: stop thinking of variables as variables; they are sets. Violence, for example, is not a variable. Violence is a set--fuzzy or crisp--into which cases represent degrees of membership. For example, thinking of Pinker's study, "war in the 1800s in Europe" is a case, along with another case such as "war in China in the 1800s." Both cases could be placed in the set "macro-level violence through war." Membership in the case could, at least initially, be defined in terms of basic rates, as Pinker uses, or converted into boolean or fuzzy set membership.

But the key point here is that they are different: they are each a case, a different, context-dependent case, which one will explore, in terms of their respective configurations, to find similarities and differences; and it is this comparative approach that will draw out the context-dependent causal similarities and differences amongst these cases. For example, in relation to Pinker's work, one may find that violence has gone down in both cases, but the reasons for the decrease in violence is different, based on differences in configuration.

Why is something like this important? Consider policy recommendations. Insensitivity to configurational differences, context and, ultimately complexity is the failure of much policy--see, for example, Applying Social Science by Byrne.

Following this argument, violence, as a complex system, reconfigured at multiple levels of scale, can be defined as a set, comprised of multiple sub-sets, each representing a type and scale of violence, from the macro to the micro. Each set is comprised of cases, which are configurations, which take into consideration context and difference. Such an approach allows one to talk about violence in a much more sophisticated way. For example, one could show how violence is increasing and decreasing, for example over time; contradictory trends. The macro-level violence of war in Europe during the 20th century is not the same thing as the macro-level violence of war in China or Africa or South America or between hunter and gathering tribes or war amongst smaller empires. They constitute different cases, different forms of macro-level violence. Studying violence this way allows us to ask much more specific questions: which forms of government or social organization in which particular contexts, for example, lead to less war? Which forms of government or social organization in which particular contexts lead to less micro-level, face-to-face violence? And, so forth.

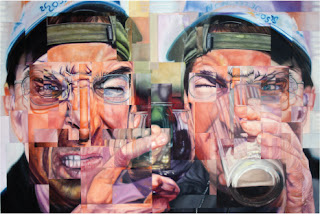

complexity art "Two Duche Bags; Or, Toast This"

This is a painting i recently completed called Two Douche-bags; Or, Toast This! It is a comedic homage to jerks everywhere who, by definition, think they are more incredible then they actually are. It is also a good example of my exploring complexity through assemblage, as it is the same set of integrated images of my nephew and brother-in-law on both side, except the one on the right was inverted and developed to become something different.

Eames Documentary

I am a huge fan of the work of Charles and Ray Eames and have been waiting for their complexity science, postmodern equivalent. Anyway, my wife sent me this link to a new documentary on them. It looks great:http://www.midcenturia.com/2011/10/eames-architect-and-painter-film.html

27/11/2011

Steven Pinker Versus Complexity

The evolutionary psychologist, Steven Pinker has published a new book: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence has Declined. I came across a review of the book in the Dec/Jan 2012 edition (Volume 18, Issue 4) of Book Forum, which, by the way, I thoroughly enjoy. It is a great periodical. CLICK HERE TO SEE THE REVIEW

I decided to quickly blog on the book because, given that this is a blog about complexity, I think Pinker’s book presents an interesting idea that works along with my previous posting about Andrew Wilson's website on complexity and psychology.

In a very ridiculous nutshell, Pinker's basic argument is that humans have progressed to a place of less violence, thanks in large measure to cultural and social forces impinging upon the better half of our evolved nature; "the better angles of our nature," as Lincoln famously stated.

Pinker's study has two historical foci: (1) the longue durée of human history and, more specifically, (2) the last 20 years of globalization-induced history.

Such a provocative thesis often requires careful review and critique. So, it is not a matter of Pinker simply being right or wrong. (As a side note, "Pinker, Right or Wrong?" seems to be the nature of most debates I have seen on the book, with little thinking in the grey area of, "hey, just how well does the model fit?")

As a complexity scientist, I am primarily interested in his notion that the world-wide decrease in violence has a scale-free character to it. Pinker argues that, from macro-level wars to micro-level views on spanking children, the world has become a less violent place both over the longue durée of human history and, more specifically, over the last 20 years of globalization-induced history.

I think further exploration of this argument is a great dissertation or study for a complexity scholar in history, anthropology, epidemiology or applied statistics to examine.

A note on method: Pinker is clear that his focus is physical violence, not violence as a metaphor for political, cultural or economic oppression. Violence as physical violence. His method of analysis is rather simplistic: rates (ratios expressed over time), computed as a basic prevalence--people harmed by violence divided by the total population. There are lots of epidemiological issues that emerge when one thinks of this approach, but we will confine ourselves to just two:

One of the immediate issues that emerges is that, as the world gets larger, large-scale violent events such as wars, by definition, decrease in their rate of harm. If there are several billion people on the planet and a world war emerges where several million people are killed, this comes across as not as bad as the Roman empire killing people in a much smaller world. Is it true, then, that, at a macro-level scale, we live in a less violent world? What, for example, if we used a network analysis approach and looked at degrees of separation. Even in a world of several billion people, are humans less separated from violence than they were 2 thousand years ago? Also, is there, perhaps, some sort of tipping point here, where the world, past a certain population threshold, becomes too large at the macro-level for people to inflict an increasing rate of violence?

And, as another issue, what about regional scale--here I am thinking of path dependency issues in terms of different complex socio-political systems bounded by particular geographies? Should one's focus be broken down into regions? For example, if one just studied Europe, would Pinker's thesis hold--particularly in terms of his argument that smart governments, not too corrupt and reasonably democratic lead to less violence? Or, is it that, at smaller levels of scale, more democratic government leads to less daily violence in the criminal justice system, people-to-people interactions, discriminatory violence, etc. But, at larger scales, particularly country to country, violence through war has not decreased? It is true that over the last 20 years macro-level violence has decreased. But, I am just not sure what to make of that phenomenon. Anyway, these are the sorts of questions that emerged in my head as I worked through Pinker's ideas.

Bottom line: I think Pinker has an interesting thesis, but I think a lot more work needs to be done before it is embraced. In particular, I think his topic is far too complex to be analyzed in terms of simple rates. It needs to be grasped in complex systems terms and truly examined for its scale-free character and regional context. My initial response is that Pinker's findings are more scale-dependent and context-sensitive than they initially seem. But, without conducting a study, it is nothing more than a conjecture on my part.

I decided to quickly blog on the book because, given that this is a blog about complexity, I think Pinker’s book presents an interesting idea that works along with my previous posting about Andrew Wilson's website on complexity and psychology.

In a very ridiculous nutshell, Pinker's basic argument is that humans have progressed to a place of less violence, thanks in large measure to cultural and social forces impinging upon the better half of our evolved nature; "the better angles of our nature," as Lincoln famously stated.

Pinker's study has two historical foci: (1) the longue durée of human history and, more specifically, (2) the last 20 years of globalization-induced history.

Such a provocative thesis often requires careful review and critique. So, it is not a matter of Pinker simply being right or wrong. (As a side note, "Pinker, Right or Wrong?" seems to be the nature of most debates I have seen on the book, with little thinking in the grey area of, "hey, just how well does the model fit?")

As a complexity scientist, I am primarily interested in his notion that the world-wide decrease in violence has a scale-free character to it. Pinker argues that, from macro-level wars to micro-level views on spanking children, the world has become a less violent place both over the longue durée of human history and, more specifically, over the last 20 years of globalization-induced history.

I think further exploration of this argument is a great dissertation or study for a complexity scholar in history, anthropology, epidemiology or applied statistics to examine.

A note on method: Pinker is clear that his focus is physical violence, not violence as a metaphor for political, cultural or economic oppression. Violence as physical violence. His method of analysis is rather simplistic: rates (ratios expressed over time), computed as a basic prevalence--people harmed by violence divided by the total population. There are lots of epidemiological issues that emerge when one thinks of this approach, but we will confine ourselves to just two:

One of the immediate issues that emerges is that, as the world gets larger, large-scale violent events such as wars, by definition, decrease in their rate of harm. If there are several billion people on the planet and a world war emerges where several million people are killed, this comes across as not as bad as the Roman empire killing people in a much smaller world. Is it true, then, that, at a macro-level scale, we live in a less violent world? What, for example, if we used a network analysis approach and looked at degrees of separation. Even in a world of several billion people, are humans less separated from violence than they were 2 thousand years ago? Also, is there, perhaps, some sort of tipping point here, where the world, past a certain population threshold, becomes too large at the macro-level for people to inflict an increasing rate of violence?

And, as another issue, what about regional scale--here I am thinking of path dependency issues in terms of different complex socio-political systems bounded by particular geographies? Should one's focus be broken down into regions? For example, if one just studied Europe, would Pinker's thesis hold--particularly in terms of his argument that smart governments, not too corrupt and reasonably democratic lead to less violence? Or, is it that, at smaller levels of scale, more democratic government leads to less daily violence in the criminal justice system, people-to-people interactions, discriminatory violence, etc. But, at larger scales, particularly country to country, violence through war has not decreased? It is true that over the last 20 years macro-level violence has decreased. But, I am just not sure what to make of that phenomenon. Anyway, these are the sorts of questions that emerged in my head as I worked through Pinker's ideas.

Bottom line: I think Pinker has an interesting thesis, but I think a lot more work needs to be done before it is embraced. In particular, I think his topic is far too complex to be analyzed in terms of simple rates. It needs to be grasped in complex systems terms and truly examined for its scale-free character and regional context. My initial response is that Pinker's findings are more scale-dependent and context-sensitive than they initially seem. But, without conducting a study, it is nothing more than a conjecture on my part.

13/11/2011

Psychology & Complexity Science Website

I recently came across this website via one of the Santa Fe listserves to which I belong. It is called: Notes from Two Scientific Psychologists A brave attempt to think out loud about theories of psychology until we get some

Here is how Andrew Wilson, one of the team of psychologists running this blog, explains their focus:

He studies "the perceptual control of action, with a special interest in learning. I had the good fortune to be turned onto the work of James Gibson, the dynamical systems approach and embodied cognition during my PhD at Indiana University. This non-representational, non-computational, radical embodied cognitive science is at odds with the dominant cognitive neuroscience approach, but provides an over-arching theoretical framework that I believe psychology is otherwise missing. My plan for my activity here is to review the theoretical and empirical basis for this approach, to organise my thoughts as I develop my research programme."

---------------------------

I just think this website is great! While my doctorate is in medical sociology, my masters is in clinical psychology, and my early research was in addiction. I love this website because it is pushing hard to move psychology in the direction of systems and complexity. For example, the idea that cognition is restricted to the brain (along with basic notions of a computational or representational mind) or that our embodied mind (which also has emotions, don't forget those things as well, along with intuitions, meaning making, immune system intelligence, etc) is not an emergent phenomenon, developmentally and bio-psychologically progressed through our symbolic interactions with our sociological and ecological systems, is (pun intended) mind-numbing. Just a little plug for symbolic interaction (going all the way back to Mead, Blumer, etc, etc) and neo-pragmatism (a good example is Rorty): these scholars, while not getting it always entirely right, have been pushing these ideas since the turn of the previous century and, in mass, for the past several decades!

anyway, check out the website.

Here is how Andrew Wilson, one of the team of psychologists running this blog, explains their focus:

He studies "the perceptual control of action, with a special interest in learning. I had the good fortune to be turned onto the work of James Gibson, the dynamical systems approach and embodied cognition during my PhD at Indiana University. This non-representational, non-computational, radical embodied cognitive science is at odds with the dominant cognitive neuroscience approach, but provides an over-arching theoretical framework that I believe psychology is otherwise missing. My plan for my activity here is to review the theoretical and empirical basis for this approach, to organise my thoughts as I develop my research programme."

---------------------------

I just think this website is great! While my doctorate is in medical sociology, my masters is in clinical psychology, and my early research was in addiction. I love this website because it is pushing hard to move psychology in the direction of systems and complexity. For example, the idea that cognition is restricted to the brain (along with basic notions of a computational or representational mind) or that our embodied mind (which also has emotions, don't forget those things as well, along with intuitions, meaning making, immune system intelligence, etc) is not an emergent phenomenon, developmentally and bio-psychologically progressed through our symbolic interactions with our sociological and ecological systems, is (pun intended) mind-numbing. Just a little plug for symbolic interaction (going all the way back to Mead, Blumer, etc, etc) and neo-pragmatism (a good example is Rorty): these scholars, while not getting it always entirely right, have been pushing these ideas since the turn of the previous century and, in mass, for the past several decades!

anyway, check out the website.

08/09/2011

Complexity, Professionalism, and the Hidden Curriculum

Just got back from the The Association for Medical Education in Europe Conference. AMEE "is a worldwide organisation with members in 90 countries on five continents. Members include educators, researchers, administrators, curriculum developers, assessors and students in medicine and the healthcare professions."

We did a pre-conference workshop on complexity method as applied to the topics of medical professionalism and the hidden curriculum. It went very well. My co-conspirators in presenting were:

1) Jim Price (Institute of Postgraduate Medicine, Brighton & Sussex Medical School, UK)

2) Susan Lieff (Centre for Faculty Development, Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Canada)

3) Frederic Hafferty (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA)

4) John Castellani (Johns Hopkins University, USA)

We also had two student presentations using social networks to analyze medical education:

O B Nikolaus*, R Hofer, W Pawlina, B Castellani, P K Hafferty, F W Hafferty. “Social networks and academic help seeking among first year medical students.” The Association for Medical Education in Europe Annual Conference, Vienna Austria 2011.

Ryan E Hofer, O Brant Nikolaus, Wojciech Pawlina, Brian Castellani, Philip K Hafferty, Frederic Hafferty. “Peer-to-peer assessments of professionalism: A time dependent social network perspective.” The Association for Medical Education in Europe Annual Conference, Vienna Austria 2011

Overall, a very successful conference.

01/07/2011

Kent State University at Ashtabula Commerical

Check it out! i am in a commercial for our campus, Kent State University at Ashtabula. Very Cool! And for those in Northeastern Ohio, consider attending our campus.

CLICK HERE to see the commercial on YouTube

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)