On 22 August 2025 I gave a seminar on my art project, Entangled, for the ISCIA Seminar series, which is hosted through the Chair in Identities and Social Cohesion, Nelson Mandela University, South Africa. The ISCIA Horizon 2055 series focused on the role art can play in reimagining and reshaping our futures, with an eye to 2055. Much thanks to Andrea Hurst and Harsheila Riga and colleagues for hosting this series and providing me the opportunity to present my art work.

For this Blog Post, I created two video from my presentation:

PART 1 is the actual art work, Entanglement, which is a 10-minute video.

PART 2 is a presentation of how I developed my Entanglement art work.

CLICK HERE to see more of my art.

CLICK HERE to see a complete list of all the tangle images used in this project.

ENTANGLED

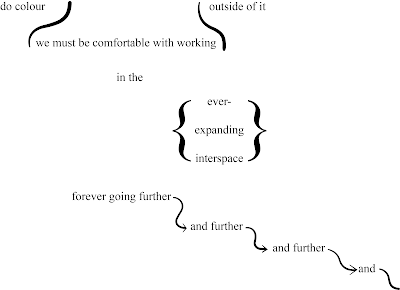

Entangled is a science fiction project that I developed, which fuses my visual art – especially the tangle sculptures and drawings, some of which are shown here – with speculative ecological storytelling. It’s grounded in my case-based complexity methods and explores how art, architecture, and adaptive technologies might help heal damaged worlds.In the story, tangles are both sculptures and semi-sentient infrastructure – somewhere between machine and living organisms, with “living threads” that adapt to ecological, social, and psychological conditions. They modulate humidity, absorb CO₂, respond to collective trauma, and serve as localised care hubs, architectural shelters, or nodes in decayed urban landscapes.

The project is deeply visual: I’ve used LLMs and AI to create photorealistic renders, gallery installations, speculative post-industrial South African environments, floating tangle habitats, and wire-mesh architectures. I’ve also developed Rhea and other characters, scientists who help uncover the tangles’ purpose and ambiguity.

But Entangled isn’t just a story. It’s also an art project and a visual complexity methodology. It brings together my work in the plastic arts, environmental science, AI, and case-based methods to imagine futures that are not just sustainable, but capable of justified healing.

Case by Case, Wire by Wire: The Visual Method Behind the Atlas

For those who have read through the Atlas of Social Complexity, you will note our extensive usage of art across most of the chapters, including images of the tangles! That is entirely on purpose. Art is for both Lasse Gerrits and me a form of visual complexity method, a way to research the social complexity in which we live and inhabit.

Once recognised, the reader will hopefully see that my project, Entangled, is a direct continuation of the ideas I’ve developed in The Atlas of Social Complexity – but expressed through a different medium.

Where the methodological theme of The Atlas outlines the formal, methodological, and theoretical basis of case-based complexity, Entangled and the tangles explore those same commitments through the plastic arts, narrative, and speculative design.

Both are anchored in a shared worldview: that complexity is best understood not as something to model from a distance, but as something we are already living inside of, as embedded agents, entangled in systems we partially shape and are shaped by.

In the Atlas, our case-based approach is grounded in critical realism – and the same for the tangles –which rejects both naïve empiricism and abstract structuralism. Instead, it argues that, at the ontological level, social systems have real, generative mechanisms—often hidden, often messy—that produce the outcomes we observe. These mechanisms are historically contingent, emergent, and embedded in configurations of material and social life. In the Atlas, we treat each topic not as an example of a system, but as a concrete instantiation of complexity: an event, a structure, a pattern that demands attention to context, history, and power.

Entangled carries that same sensibility into the visual domain. Each tangle I create is a material case—a sculptural system, a visual hypothesis. They are not metaphors for complexity; they are complexity rendered through form. Their wires and threads suggest systems of interaction, feedback, adaptation, breakdown. Their placement – in landscapes, galleries, speculative architectures – stages the unequal terrain of social life. Some tangles offer protection; others expose fragility. They model differentiated complexity, just as the Atlas does.

But this project adds something else: it makes space for embodied cognition and emotional and existential understanding. The tangles are not diagrams. They provoke response. They ask us to feel our way through the systems we study – to sit with uncertainty, asymmetry, and emergence. This matters politically. As both Entangled and the Atlas make clear, complex systems are not neutral. They reproduce inequality, power, oppression, cruelty – but also freedom, liberty, diversity and healing. They encode histories of dispossession and structural violence, and also moments of wellbeing and happiness. And they rarely offer easy solutions.

That’s why Entangled is not utopian. The tangles don’t fix the world. But they do propose a different mode of engagement – one that’s grounded in the complexity of lived experience, one that recognises that any healing worth pursuing must begin with the realities of entangled life: patterned, uneven, partially knowable, and still, somehow, open to transformation.

CLICK HERE to see more of my art.

CLICK HERE to see a complete list of all the tangle images used in this project.