QUICK OVERVIEW AND LINKS TO THE OTHER THEMES AND CHAPTERS IN THE BOOK

The first major content theme in The Atlas of Social Complexity is Cognition, Emotion and Consciousness. This first theme includes six chapters, which I have so far blogged on. Chapter 6 addresses autopoiesis. Chapter 7 turns to the role of bacteria in human consciousness. Chapter 8 explores how the immune system, just like bacteria and cells, is cognitive – and the implications this has for our wider brain-based consciousness. Chapter 9 explores a complexity framing of brain-based cognition, emotion and consciousness. Chapter 10 explores the complex multilevel dynamics of the Self. Chapter 11 is about human-machine intelligence.

The second major content theme in The Atlas of Social Complexity is The Dynamics of Human Psychology. So far for this theme, I’ve given a basic overview, found here. I then moved on to the first theme, Human psychology as dynamical system (Chapter 13). From there I reviewed Chapter 14: Psychopathology of mental disorders ; Chapter 15: Healing and the therapeutic process; and Chapter 16: Mindfulness, imagination, and creativity.

The third major theme is living in social systems (Chapter 17). The first chapter in this section is Complex social psychology (Chapter 18). From there we move on to Collective behaviour, social movements and mass psychology (Chapter 19). Next is Configurational Social Science (Chapter 20). From there we move to the Complexities of Place (Chapter 21); followed by Socio-technical Life (Chapter 22). Chapter 23 turned to the theme of Governance, Politics and Technocracy. Chapter 24 focused on The Challenges of Applying Complexity. Chapter 25 focused on Economics in an unstable world. And, finally, Chapter 26 focused on resilience and all that jazz. Chapter 27 introduces the final theme of the book, Methods and complex causality. It begins with Chapter 28, Make Love, Not Models and then moves on to the current chapter.

The focus of the current chapter (Chapter 29) is Revisiting Complex Causality.

OVERVIEW OF CHAPTER

|

| This is an artistic piece not to be taken literally |

Reimagining Causality: Drawing Vectors through the Clouds

In Chapter 29 of The Atlas of Social Complexity, we revisit one of the most unsettled and yet foundational issues in the social sciences: causality. The standard scientific imagination tends to render causality as a linear vector, as if social life were a giant billiard table of variables, each bouncing off the next. But for those of us working in the complexity sciences, this simply will not do. As we argue here, causality must be approached as a pluralistic, creative, and often contradictory terrain.

A quick caveat before proceeding:

Lots of social science research is not linear -- grounded theory method, ethnography, systems mapping, etc. But, if you use statistics, you are using a linear model – unless you do curve fitting or growth mixture modelling, etc. And, even when folks use differential equations, they tend to linearize, the power law is a good example. So, complexity can also be critiqued for reductionism. Econometrics also enjoy linear models, as does engineering, medicine, public health. So, yes, the Newtonian model is still dominant. (please disagree) We suggest other ways of viewing complex causality in our Chapter and in this final section of The Atlas. We are interested in multi-finality, equi-finality and causal asymmetry issues, which confound models that don’t explore multiple trajectories. In terms of vectors, we combine the algebraic notion of vector (a configuration of factors) with the physics notion of a vector (a point with direction velocity), through the idea of a case, and we then employ machine learning, network analysis, systems mapping, ABMs to study the complex trajectories of phase spaces, and we take a dynamic nonsequential approach to time. We hope that makes sense.

For those interested in work beyond our chapter, we highly recommend, The Routledge Handbook of Causality and Causal Methods. Edited By Phyllis Illari, Federica Russo

With that said, let's explore some different ways of thinking about complex causality.

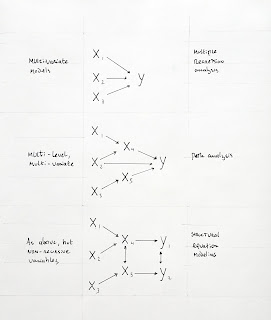

Methods = Implied Causal Assumptions

Our starting point is clear: every method carries an implicit theory of causality. Whether one draws on regression, simulation, or participatory systems mapping, each technique brings its own assumptions. The problem is not method per se, but the failure to interrogate those assumptions. A method may claim to model social dynamics yet reduce it to a cartoon version of complexity. This chapter urges a return to the sociological imagination as a methodological resource, not just a theoretical flourish.

Vector and Circular Causality

Much of social science is still working with a Newtonian imagination of cause preceding effect. Yet, as any student of systems theory knows, life rarely moves in straight lines. Feedback loops are not exceptions but the rule. As we show, causality in complex systems is circular. Obesity models, policy interventions, and emotional regulation all resist temporal sequencing. Consequences feed back into causes. We are not arguing for chaos but for an approach that acknowledges entanglement and co-determination. Participatory systems mapping and causal loop diagrams offer one way forward.

Set-Theoretic and Configurational Causality

Another path draws from set theory and multiple conjunctural causation. Rather than treating variables as inputs to be isolated, set-theoretic approaches recognise that outcomes emerge from configurations. Causes do not act in isolation. They co-occur, reinforce, and sometimes cancel each other out. This logic is asymmetric: what explains the presence of an outcome does not necessarily explain its absence. In this respect, set theory is more honest about the conditional and context-bound nature of social life.

What If We Let Go of Causality?

A radical proposition: what if we stopped trying to pin causality down altogether? Postmodern critiques, often dismissed as anti-scientific, offer a valuable reminder. Humans are not particles. They are reflexive, symbolic actors whose experiences are shaped by meaning, power, and interaction. Symbolic interactionism, with its focus on lived experience and situated action, invites us to study emergence from within. The goal is not objectivity as abstraction but understanding as situated knowledge.

Time, Events, and Cases

To take social complexity seriously is to take time seriously. Not clock time, but lived time. Not fixed intervals, but trajectories. Cases evolve, bifurcate, and diverge. This demands methods that can capture within-case variation, not just population-level trends. Emergence, equifinality, and multifinality are temporal phenomena. They reveal that social systems are less about being and more about becoming.

Vectors as Art

Finally, we arrive at the metaphor of the vector not as scientific instrument but as artistic gesture. Drawing vectors through a cloud of data is as much about intuition and aesthetic sensibility as it is about logic. Listening to an old cassette tape or observing a Mondrian painting, we are invited to find meaning in pattern and absence, connection and void. Causality, in this light, becomes a form of disciplined imagination.

This is not an argument against science. It is a call for a deeper science—one that lives up to the messiness of the world it claims to study.